May 14, 2020

Faculty at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC/CUNY) are helping students feel connected to their course content and each other — in what is arguably the most challenging semester yet, of their academic lives.

This past March, midway through the Spring 2020 semester and in response to a statewide stay-at-home directive, all CUNY classes moved to a distance-learning format.

As the COVID-19 outbreak ravaged their neighborhoods, students who were able to do so, picked up laptops and IPads at BMCC to use during the semester. Faculty accessed resources, consulted with each other and set about moving their instruction to platforms including Open Lab, Blackboard and Zoom.

What happened next was a process of discovery; sometimes frustrating, sometimes exciting.

Professors have created structure and support for their students with weekly updates, lecture videos, virtual breakout rooms and other tools. Students have risen to the task, gradually embracing the new reality of their college education.

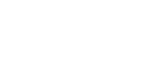

Face-to-face contact — even if it’s virtual — helps students learn coding and share their process

Computer Science Professor Hao Tang has led BMCC students through complex problem solving as part of his researchproject to develop crowd behavior simulation software, based on surveillance footage in New York City transportation hubs. Students also joined Tang to explore how mobile technology can assist the blind in navigating through a public setting.

The latest problem Hang has tackled with his students, is how to learn coding and other concepts in a virtual format.

His course load includes Introduction to Computer Applications — which was already an online course — and two classes that switched to distance learning in March: one on programming languages, and another on Geospatial Information Technology.

“It was difficult at first,” Tang says. “If we are in the same room, I can tell who is confused after I explain a concept. I can see it in their faces and body language. Now with Zoom, I ask a lot of questions to see if they understand the concept. I tell them to turn on their cameras so I can see them and so they can see my face — but it’s not the same.”

Tang created a sense of classroom community using a variety of strategies.

“I send emails individually if a student seems to be struggling or not participating,” he says. “BMCC has a platform, Connect2Success, through Starfish, and I use that to reach out to students whose attendance is not good. Through Starfish, an advisor can also reach out to the student.”

As the students began to feel more connected to each other, it became easier to focus on new concepts, though some logistical challenges remained.

“Once the class went online, it wasn’t possible to go to each student individually and look at their code on their computer screen and help them manipulate it,” says Tang. “To learn a programming language, you have to learn syntax. You have to trace the code line by line — so what I do is I draw on a digital tablet and screen share what I’m doing, using a stylus so the students see it in real time.”

Tang also utilizes the remote feature on Zoom. “The student can share their screen, share their code with me and with other students,” he says. “I try to focus on the kind of common problem that coders will encounter in a job.”

The process gradually became more comfortable for both Tang and his students.

“At first I didn’t realize there was a group discussion feature in Zoom,” he says. “I learned about it from a colleague; we’re always talking about this. Now, I can make a breakout room for small groups, and my students like that a lot. I make six rooms, each one with two or three students.”

He explains that students who feel nervous about sharing their coding problems with the large group will do so more readily in a breakout room. “Meanwhile I can drop in on the breakout rooms to check on them,” he says. “I always enable the video so they know I’m there.”

When the breakout rooms come back together at the end of class, “Everybody is all excited,” Tang says. “I always thought I needed a lot of interaction, but then I learned how to engage in this new way. Both the students and me are learning.”

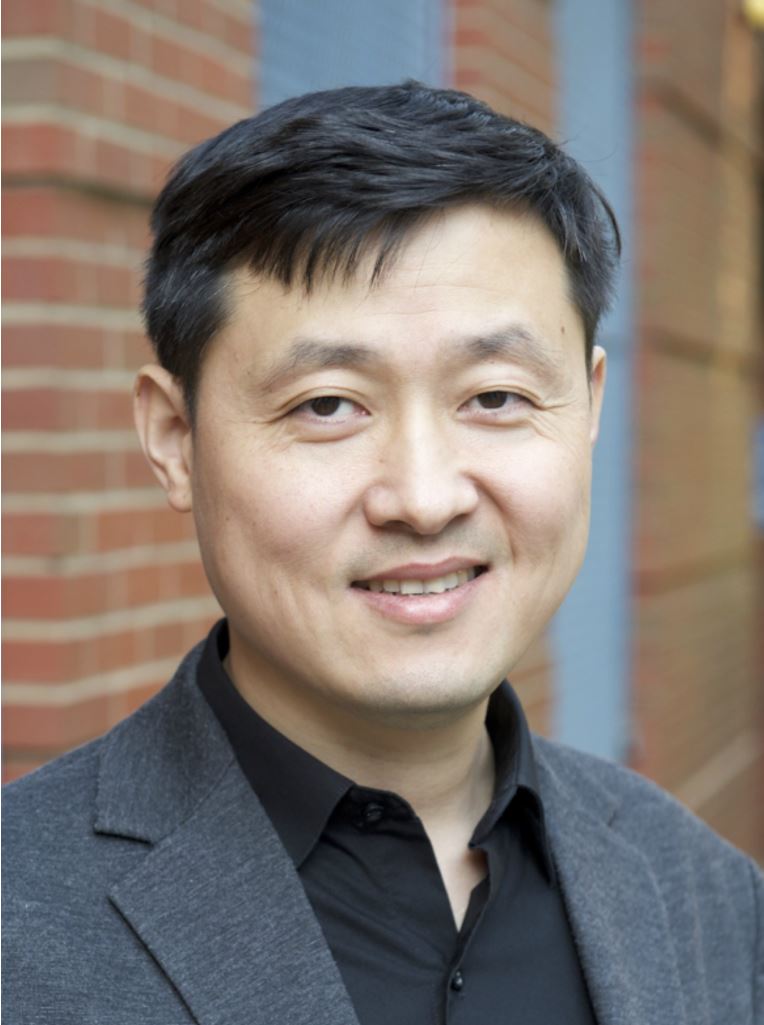

Translating successful math classroom dynamics to an online format

“Teaching online is not new for me but transitioning within one week was new,” said Mathematics Professor Barbara Lawrence. “I had to decide how I could keep the dynamics and pedagogy that I presented in person, in a distance format.”

One of these dynamics involved giving students immediate feedback.

“In the past, I had always collected, graded, scored and returned homework from all my classes during our session,” Lawrence says. “It was my way providing individualized feedback. Students loved this because it encouraged them to challenge themselves. I always engage my students through questioning and having them work out problems on the board. This engagement had to be recreated another way.”

During Zoom sessions, Lawrence presents problems for students to solve, and replicates her process of circulating through the classroom.

“I click on a name and ask for a response,” she says. “I also record my lectures and post all written notes on the online course management system Blackboard after each Zoom session, so students can review what they learned, at their own pace.”

These zoom sessions “closely resemble my in-person lectures,” Lawrence says. “I give historical background of the mathematics concepts as a hook to gain the students’ interest and make connections among the previous concepts when starting my lessons.”

To create structure, Lawrence uses the WebAssign function in Blackboard, where she also posts course updates and upcoming exams using the Announcement tab.

“Students have two hours to download the exam, work out problems and then upload back on the Assignment tab of Blackboard,” she says.

As for adding Zoom functions to the class experience, “Learning its capabilities was a little challenging at first, but once I was able to share documents along with writing in real time on the shared-screen whiteboard, I stayed with Zoom,” Lawrence says. “I explored Blackboard Ultra recently, but will stay Zoom.”

Overall, she says, students have stayed engaged with her class, though some have faced more difficulties that others.

“Many students don’t have the resources to participate in online sessions because of equipment and internet access,” she says. “Many are parents and must assist their children with their classes.”

Even so, “Learning math online can be successful if students are able to participate in the Zoom sessions,” Lawrence says. “I believe this is the key. Students have made it very clear that they cannot teach themselves math. I also believe that given a choice to take an online math class, students will be committed and succeed. If they are forced to transition, fewer students will be successful.”

Building community, Lawrence says, is possible “with established groups and very structured assignments. This can occur and be monitored in the Discussion Board of Blackboard. This is a place where students can engage in group work and review topics before exams, solving and discussing review exercises together.”

Blending low- and high-tech techniques to impart animation concepts and skills

“We’re using the same Adobe software we had in the lab, except not enhanced by the interactive pen displays we had there,” says Anna Pinkas, a professor and multimedia artist who teaches Introduction to 2D Animation in the BMCC Media Arts and Technology department.

Access to software the students had been using in class before the switch to distance learning was made possible when Adobe offered free licenses to CUNY students and others, through May 31.

“I already had a license at $25 a month, but that wasn’t doable for our students,” Pinkas says. “The temporary, free license allowed my students to download Adobe Animate CC and AfterEffects, the software they were getting used to when we switched to distance learning.”

Staying up to date with software is important, she says, with a few caveats.

“Learning industry standard software is important but the software’s going to change,” she says. “By the time these students graduate it will be a new version, or maybe the place where they’re interning is using something different. So I have to ask, how can we drill down to essential principles that are applicable in different softwares and across platforms?”

Pinkas’s students are also using techniques that harken back to her own college years as an animation major, and reflect insights she has gained since then, in her fine arts career.

“When I completed my bachelor’s degree, almost 15 years ago, we didn’t have a lot of these tools,” she says. “It was much more analogue. I did a lot of paper cut outs, flip books, stop-motion and all of that.”

Speaking as an artist, “The tension between analog and digital at play in my work is a reflection of our daily experience of being torn between our screen-based reality and our tangible one,” she says. “Digital tools are essential, but they are also the very thing I attempt to escape by imbuing my work with traces of the human hand.”

Speaking as a teacher, she reflects on ways low-tech methods can help students engage with concepts as they are distance learning.

“Students who are animation majors love to draw, so I’ve been giving them options like flip book and stop-motion assignments,” Pinkas says. “These are animation techniques that have been used since the advent of cinema.”

The students make flip books with three-by-five cards or by drawing an evolving image on the corner of a notebook, and make a video of the result with their phones, to submit for an assignment.

“I think resiliency and having constraints can lead to interesting solutions,” Pinkas says.

She points out that in some areas, like graphic design and web development, “things can look very sophisticated pretty early in someone’s career path — but it can also start looking like all the portfolios look the same.”

On the other hand, encouraging students to think of low-tech solutions “can sometimes result in interesting solutions, that I think would stand out in a portfolio and set that student apart.”

Another technique Pinkas and many other instructors use in their distance-learning classes is to video herself on Zoom and post the tutorial for students to view.

“It’s not that polished; sometimes I make mistakes, but that’s okay,” Pinkas says. “This week, the students are adding a background to their animations, so I show them in the video: ‘Here’s my background file, and here’s how I drop it in.’ I show them step by step — ‘now you go to this menu item and select this option.’ I share my screen to show the same interface they’re looking at when they do the assignment themselves.”

Pinkas also sends a weekly email to her students, with links and resources.

“I’m using Open Lab, BMCC’s new initiative,” she says. “I have a whole website for both courses. with slides on core concepts and terminology, web resources like tutorials, articles and videos, and assignment guidelines. It’s WordPress-based so it’s easy to use — you don’t have to be into web development at all to use it.”

So far, this platform has worked well in her class.

“What’s cool with Open Lab is that students can post their work, write a little bit about it and comment on each other’s work. It facilitates sharing work with peers,” Pinkas says. “I find much of the work impressive.”

On the other hand, when students have a hard time with an assignment, “they email me, and we come up with a solution,” Pinkas says. “Tonight I’m meeting with a student who is struggling. I asked him to send his files and I’m going to take his files, share my screen and show him what he has to do. Typically in your face-to-face class, they would struggle, and they wouldn’t go to tutoring. They might not even tell me until the assignment is due. Now, they email me as soon as they hit a problem.”

There are, of course, limits to distance teaching.

“I can’t go physically sit next to my students and look over their shoulders,” Pinkas says. “If there’s a collaborative project, helping them have the discipline to meet up outside of class, is hard. There are however, many ways of doing group projects online, and now that I’ve prioritized their technical needs and making sure they get the skills they’re supposed to acquire in these classes, collaboration and group dynamics are things we as faculty can brainstorm around, this summer.”

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- In mid-March, all CUNY classes moved to a distance learning format, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and statewide stay-at-home directive

- Faculty are finding ways to take what worked in the classroom, to a virtual setting

- Using Open Lab, Blackboard, Zoom, Starfish and other platforms, they are building community, enabling students to work in small groups and more